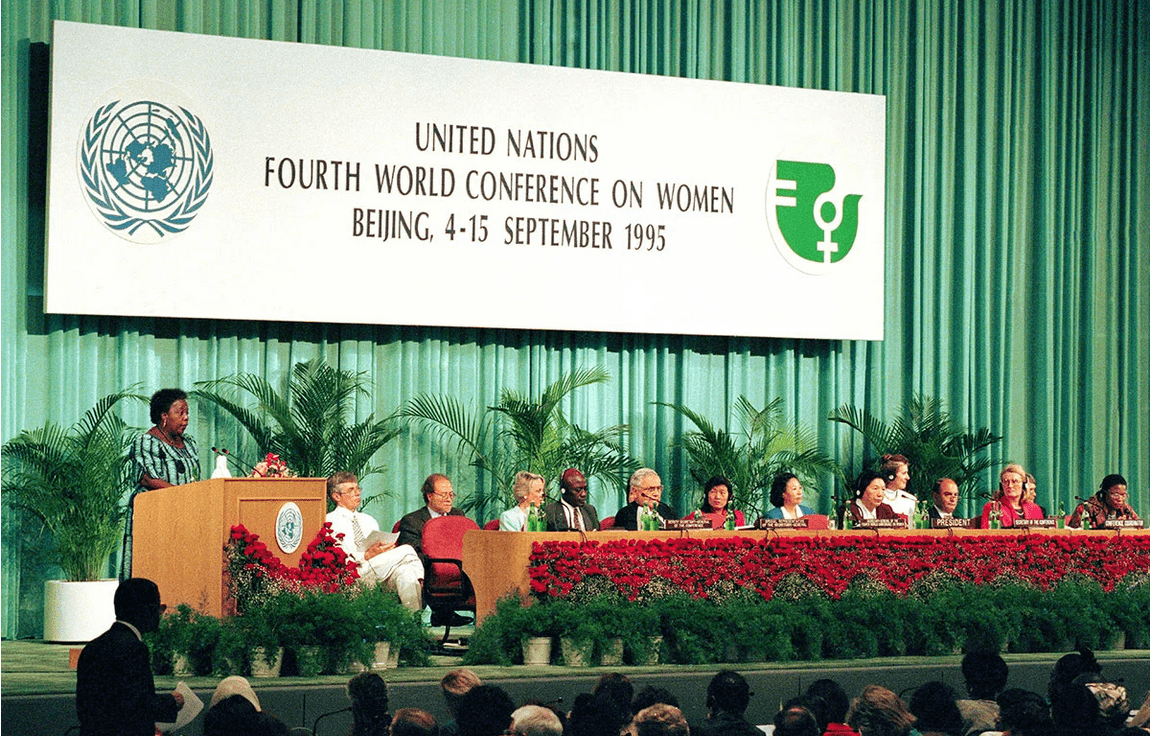

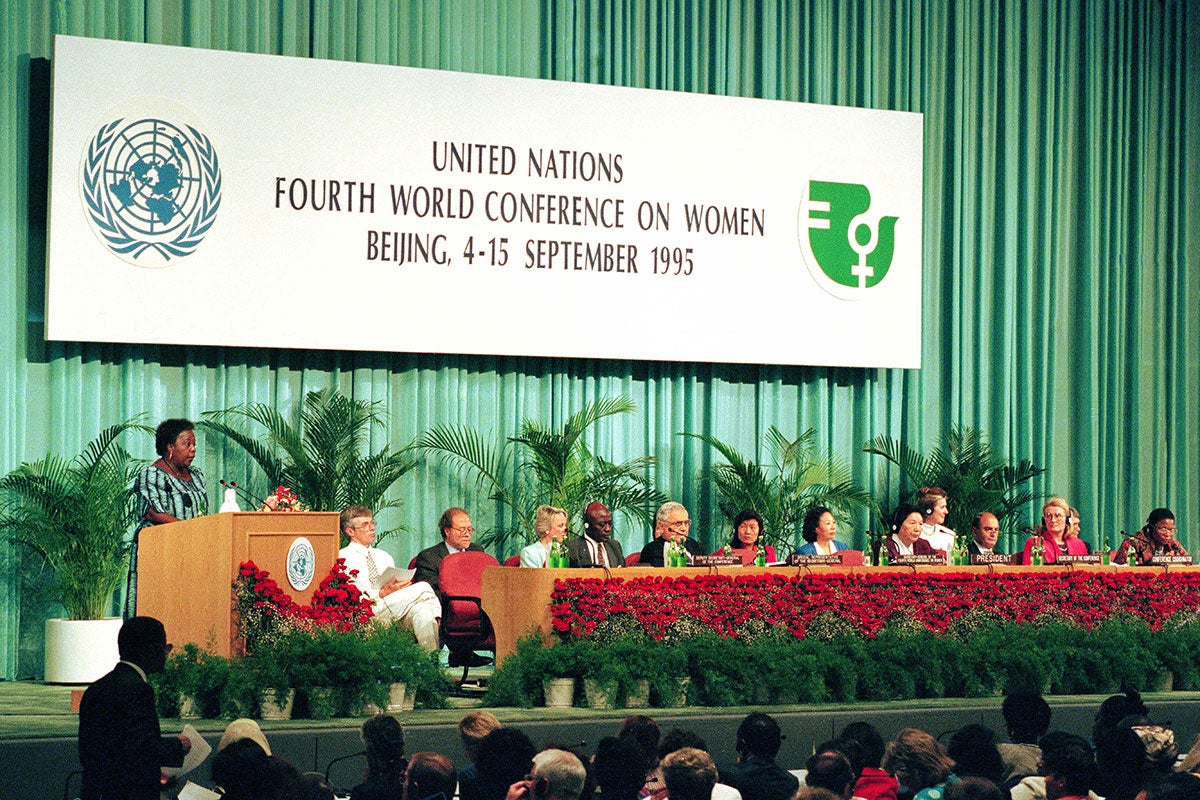

Thirty years ago, at the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, leaders from 189 countries and over 30,000 activists came together to create a visionary roadmap for achieving equal rights for women and girls. This roadmap, known as the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, became the most widely endorsed global agenda for women’s rights.

Rooted in the experiences and demands of women and girls, the Beijing Declaration outlined 12 critical areas for action, including violence against women.

As we approach its 30th anniversary in 2025, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action remains a cornerstone in the movement for women’s rights and gender equality, with governments, activists, and the UN evaluating progress, addressing challenges, and committing resources to implement the agenda.

For the 16 Days of Activism Against Gender-Based Violence, learn how the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action transformed the agenda for ending violence against women and girls, and what that means today.

Women’s Rights Are Human Rights: A milestone for gender equality

The 1993 UN World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna marked the first time women’s rights were explicitly recognized as human rights.

“Human rights are women’s rights and women’s rights are human rights” became a rallying cry for feminists at the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing. The slogan came from a speech delivered by the then First Lady of the United States of America, Hillary Rodham Clinton.

The Beijing Platform for Action affirmed women’s right to live free of violence.

The conference was the staging ground for feminists to organize and advocate for the ratification of another key international agreement—the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1979, and its Optional Protocol—a measure that was finalized in 1999 and enabled individuals to report violations directly to the CEDAW Committee. This created political pressure on governments to address violence against women and girls.

That women’s rights are human rights is not up for debate today, but with one in three women experiencing violence in their lifetime and a woman intentionally killed by an intimate partner or family every 10 minutes, no country has fulfilled the promise of a life free of violence against women.

Domestic Violence Laws: A post-Beijing surge

In 1994, around 12 countries had legal sanctions against domestic violence.

After the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, this number grew rapidly. Today, UN Women’s Global Database on Violence Against Women lists 1,583 legislative measures across 193 countries, including 354 targeting domestic violence specifically.

Research indicates that adoption of international and regional human rights agreements and feminist social mobilization spurred action in introducing progressive laws and policies.

Today there is ample evidence that domestic violence laws reduce intimate partner violence. Countries with such laws report a prevalence rate of 9.5 per cent, compared to 16.1 per cent in countries without domestic violence legislation. However, enforcement remains a challenge, with gaps in comprehensive legal protection and survivor support services.

Changing social norms and expanding essential services for survivors

The Beijing Declaration was groundbreaking in addressing violence against women and girls holistically. It called for expanded access to essential services, including shelters, legal aid, medical care, and counseling. Before 1995, only 19 institutional mechanisms for domestic violence existed; over 95 per cent of such mechanisms were established post-Beijing Platform for Action.

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action also emphasized prevention, urging governments and international development actors to invest in education and awareness campaigns that challenge social norms and stereotypes that allow violence against women to persist.

Why data on violence against women matter

What doesn’t get counted, stays invisible. Without quality data on violence against women and girls, policies and laws cannot sufficiently address the reality that women face every day.

Before 1995, most data on violence against women came from small, ad-hoc studies. The 1993 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women had called on governments to collect data on violence against women, especially domestic violence. The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action also called for systematic data collection, leading to national surveys and international studies like the WHO Multi-Country Study on Domestic Violence.

From 1995 to 2014, 102 countries conducted national surveys on violence against women.

Today, we have global initiatives like UN Women’s Women Count programme and the Global Database on Violence Against Women, which track progress and highlight areas needing urgent action. Since its inception in 2016, the Women Count programme has been supporting countries to collect more data on violence against women and has also been on the forefront of establishing a framework for measuring technology-facilitated violence.

The power of feminist movements and women’s organizations

The Beijing Platform for Action recognized the power of feminist movements and civil society in shaping policy and supporting survivors. Research confirms that the presence of a strong and autonomous feminist movement is the most critical factor to drive change in ending violence against women and girls.

Yet, in 2022, countries spent less than one percent of development aid to address gender-based violence, and only a fraction of that reached women’s organizations.

The UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women, managed by UN Women on behalf of the UN system, is the only global grant-making mechanism dedicated to initiatives focused on ending all forms of violence against women and girls. In 1996, the UN General Assembly resolution 50/166 called for the establishment of the UN Trust Fund in accordance with the measures set out in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action. As of today, the UN Trust Fund has awarded USD 225 million to 670 initiatives in 140 countries and territories.

Additionally, the Generation Equality Action Coalition on Gender-Based Violence is working towards increasing national funding to girl-led and women’s rights organizations by USD 500 million by 2026. This has resulted in game changing commitments like the new UN Women ACT to end violence against women programme through a EUR 22 million investment by the EU in strengthening women’s rights movements and their advocacy.

Championing girls’ rights: Then and now

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action was the first global policy document on women that included a specific focus on girls’ rights and addressed violence against girls.

It called for governments to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child, ensure birth registration and national identity for girls, and advance girls’ access to Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education and skills training. It also set forth actions to protect girls from gender-based violence, including practices such as child marriage and female genital mutilation and teen pregnancy—issues that still restrict girls’ rights, health, and well-being today.

While progress has been made, new challenges like climate change and online harassment are exacerbating violence against girls, as the latest UN Secretary-General’s report shows.

With nine million girls at risk of being married as children by 2030, and 1 in 4 adolescent girls experiencing abuse by a partner by the time they are 19 years old, the Beijing Platform for Action remains a vital blueprint for safeguarding girls’ rights and ensuring their voices are heard.

Source:news.un.org