In March 2024, trade ministers from around the world formally recognized the contribution of women’s participation in trade to advance economic growth and sustainable development in the Abu Dhabi Ministerial Declaration at the World Trade Organization’s 13th Ministerial Conference. Yet women still face various barriers preventing them from fully participating in trade.

The recently published Women, Business and the Law (WBL) Brief “Women, International Trade, and the Law: Breaking Barriers for Gender Equality in Export-Related Activities” sheds light on the impediments embedded in national laws restricting women’s participation in export activities. The Brief explores the relationship between equal rights across gender, and women’s participation in exporting firms as owners, managers, and workers. It further presents strategies to narrow gender gaps in trade, notably through gender equality laws, trade policies, and preferential trade agreements.

504 legal barriers to women’s participation in international trade

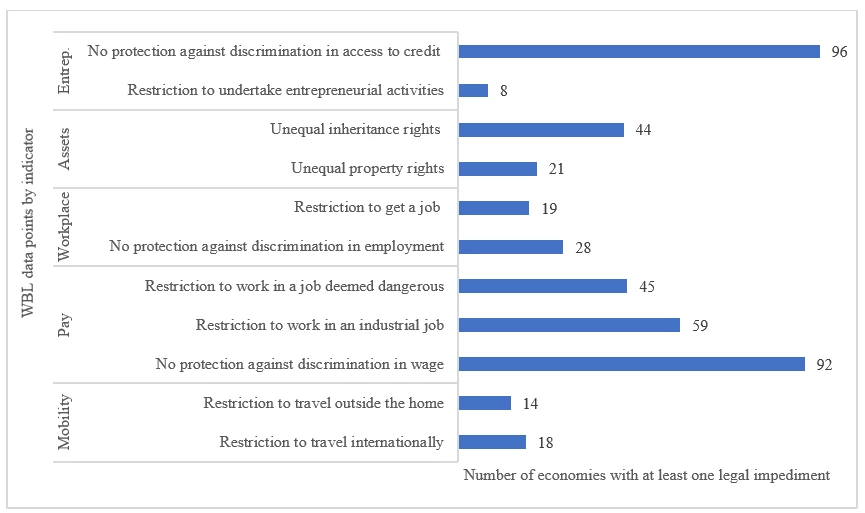

Using the WBL 2024 Index, the Brief identifies 504 legal impediments in 145 economies that can exclude women from export-related activities or set unequal conditions for them to participate in international trade in the same way as men (Figure 1).

Women face legal discrimination in trade through various means, including the inability to sign export contracts or register a business, such as in Equatorial Guinea, or restriction to trade across borders, as seen in Qatar, where women need their husbands’ permission to travel abroad. Other forms of discrimination are found in laws that give fewer property and inheritance rights to women, like in Cameroon, impeding their ability to build assets and secure capital to bear trade costs, expand their businesses, and stay competitive. Additionally, the laws of 77 economies prevent women from equally participating in the workforce of exporting firms by prohibiting them from working in certain industries or holding certain jobs. A notable example is the Russian Federation, where women are barred from employment in oil production, hence being excluded from an industry that constitutes 42 percent of Russian exports and is valued at over USD 7.3 trillion.

Figure 1. Legal discrimination limiting women’s participation in international trade measured in Women, Business and the Law 2024.

Note: Some WBL data points are combined in the figure for conciseness.

Source: Women, Business and the Law (WBL) 2024, as used in Laperle-Forget and Gurbuz Cuneo (2024).

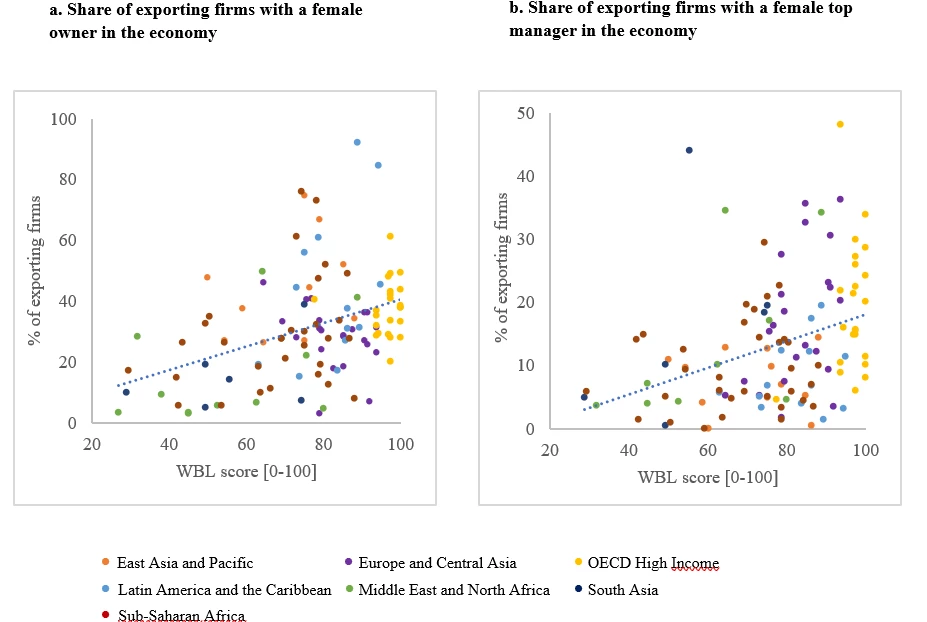

More women-owned exporting firms are associated with economies that have more gender-equal laws

Using sex-disaggregated data on the ownership and management of exporting firms from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys, the Brief provides suggestive evidence that legal discrimination against women matters for their participation in trade. As shown in Figure 2, there is a positive and significant association between women’s legal rights, as reflected by a higher WBL index score, and the share of women-owned and women-led exporting firms.

Figure 2. Economies with fewer gender-discriminating laws are associated with a higher share of women-owned and women-led exporting firms.

Note: Firms exporting at least 10 percent of sales are defined as “exporting firms.” The data uses an economy’s most recent Enterprise Survey and the WBL score from the corresponding year. Higher WBL scores indicate greater gender equality. The estimated coefficients between WBL score and the share of exporting firms with female owners (panel a: β= 0.39, t-stat=6.03) and with a female top manager (panel b: β=0.21, t-stat=4.62) are found to be statistically significant (N=116 and N=118, respectively). These statistical relationships should not be interpreted as causal.

Sources: Women, Business and the Law dataset and World Bank Enterprise Survey as used in Laperle-Forget and Gurbuz Cuneo (2024).

The Brief also examines women’s participation in exporting firms in terms of legal discrimination measured by specific WBL indicators. It reports a significant difference of 14 percentage points in the share of women-owned exporting firms between economies in terms of laws discriminating against women in access to assets and about 7.5 percentage points difference between economies in terms of legal impediments to female entrepreneurship. Similarly, the share of exporting firms with female owners is 8.3 percentage points higher in economies where laws do not limit the range of jobs women can hold than in economies with such restrictions. Furthermore, the share of full-time female workers in exporting firms is positively associated with women’s freedom of movement, with a difference of 6 percentage points in economies with no legal restrictions to mobility, although the relationship is not strong.

The way forward: eliminating legal discrimination against women to promote inclusive trade

While these relationships should not be seen as causal, they suggest that removing legal discrimination against women can facilitate their engagement in international trade. The Brief highlights leading examples of strategies in this regard. For instance, as captured in the WBL 2024 report, Azerbaijan, Malaysia, and Sierra Leone removed all legal restrictions on women’s employment over the past year, granting them equal opportunities to work in exporting firms, which are often associated with higher wages. Trade policies can also help advance gender equality, notably through the inclusion of gender-related provisions in preferential trade agreements, which have been found to have positive results on narrowing the gender pay gap and female employment. Still, the significant gender disparities in export activities call for multifaceted strategies to address the persistent challenges faced by women in trade and unlock the potential of women’s participation in trade to boost economic growth and sustainable development.

The author thanks Alev Gürbüz Cuneo, the co-author of the Brief, for her contribution to this research. Support for the work was provided by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Source:https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/