Women in The Gambia face high levels of female genital mutilation (FGM), period poverty (an inability to afford menstrual hygiene products), and domestic violence. In an interview with UN News, Ndeye Rose Sarr, the head of the UN reproductive and sexual health agency (UNFPA) in the country, underlines the challenges they face, and the efforts the UN is making to address the issues.

Ndeye Rose Sarr When a girl starts to menstruate, that’s when the problems usually start. From the age of 10, she begins to be looked at as a potential bride for an older man. And if she has not yet undergone FGM, there will be those in her community who will want to make sure that she does.

The rate of FGM in The Gambia is around 76 per cent in the 14 to 49 year age range, and about 51 per cent for girls up to the age of 14. That means that, on average, every other young girl you see in The Gambia has undergone this mutilation, which involves altering their genitals by cutting the clitoris or labia.

This leads to health consequences later in life. When they give birth, they may encounter complications, and the chances of a stillbirth are higher. If the baby survives, they may end up with obstetric fistula, holes that develop between the vagina and the bladder, that make women urinate when they sit. This can lead women being excluded from their communities, and their husbands to leave them.

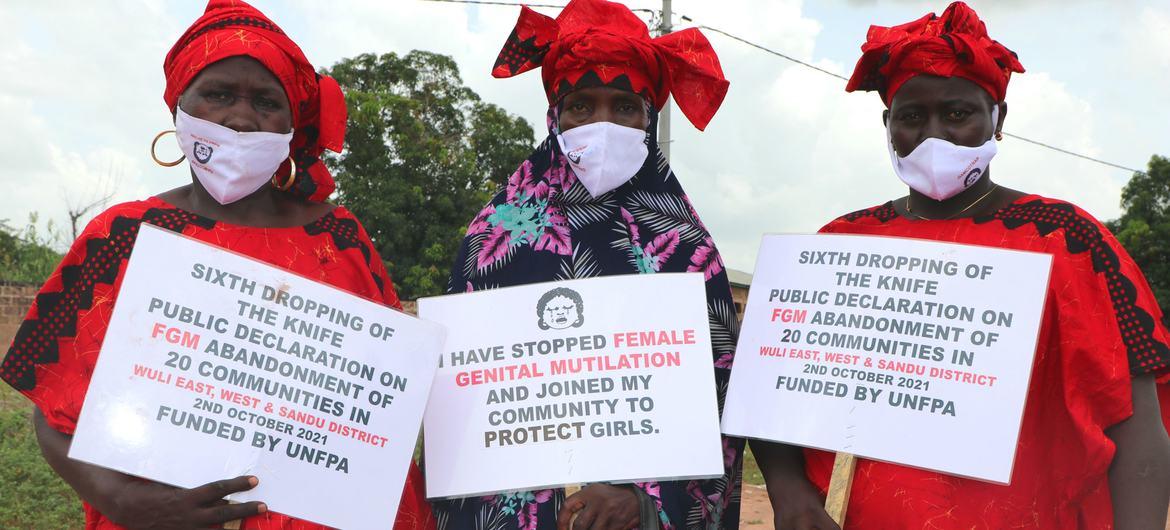

‘Women are the ones practicing FGM’

Women are the ones practicing FGM. It is usually a grandmother, the keeper of the tradition in the family. Gambians living abroad will even bring back their children to be subjected to FGM. And men will tell you that this is a “women’s thing.”

What we are looking to do is engage men and boys. We are in a society where decision makers are men; they are husbands, traditional leaders, religious leaders who will indicate what to do and what not to do in society.

We want every young man in this country, all the men, whether they are fathers, husbands or traditional leaders in their community, to say no to the practice. We have studies that show that, in countries where men have become involved, the rates have gone down.

UN News: How long, realistically, will it be before we can see the end of FGM in this country?

Ndeye Rose Sarr: FGM has actually been illegal since 2015. However, only two cases have been brought to justice since then, with no convictions.

There has to be enforcement of the law. And the willingness of the government to continue prosecuting and also helping us with increasing awareness of the problem is key.

We also need to engage at a community level. Rites of passage for girls are important, but we don’t have to go to the extreme of female genital mutilation. We can find innovative ways to create rites of passage, just as it is boys in this part of the world. It doesn’t have to be harmful, and it doesn’t have to be something that invades the bodily autonomy of the person.

Currently, it is even carried out on babies; you can’t tell me that a baby girl knows what she’s going through, and is able to consent.

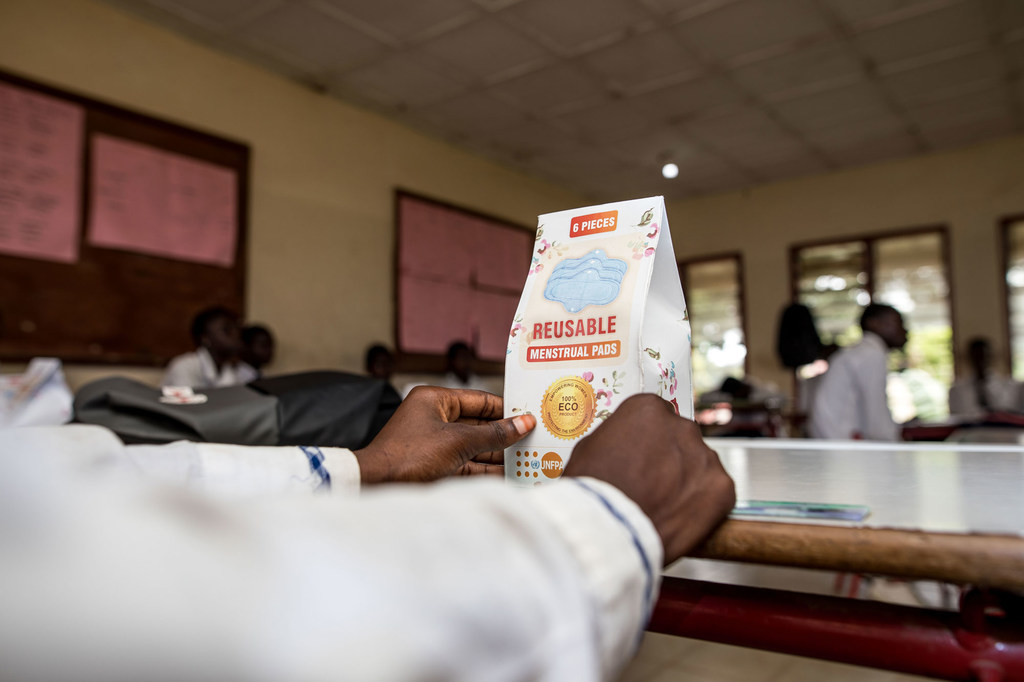

UN News: Period poverty is also widespread. What can be done to address it?

Rose Ndeye Sarr: Yes, period poverty is an issue across The Gambia, but it’s acute in rural areas, where women are less likely to have access to sanitary pads.

Period poverty leads to girls skipping school for around five days every month because, if they don’t have access to adequate menstrual products, they worry about staining their clothes, and being shamed; that’s between 40 and 50 days in a school year.

Boys will therefore have an advantage because they will be attending school more often than the girls, who are more likely to drop out of education.

So, we developed a project in Basse, in the Upper River Region, to produce recyclable sanitary pads. This is a way of empowering young women in the community, who now have a secure job, learning new skills, and improving the menstrual hygiene of women and girls.

We go to schools to distribute the pads and, when we’re there, we take the opportunity to talk about bodily autonomy, and comprehensive health education, so that the girls know more about their bodies, what is happening to them, what is okay, what is not okay. I think we are making a difference in Basse.

We need to understand that there are girls in this world who don’t have access to menstrual health and hygiene and who don’t have access to menstrual products when they have their menstruation. And we need to put an end to that.

Source:news.un.org