UNITED NATIONS, New York – Over the past 30 years, global commitments to sexual and reproductive health and rights have made remarkable advances: Maternal death rates have dropped by almost a third, the number of women using modern contraception has doubled and more than 160 countries have passed laws against domestic violence.

A new report by UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency, traces the path that led to this progress and empowered millions with increased freedom and autonomy. But it also lays bare how little these improvements have affected the world’s poorest and most marginalized, for whom rights and choices remain largely out of reach.

These disparate realities are driven by inequality and discrimination, often hidden within our health systems and economic, social and political institutions. Achieving equity, then, requires exposing inequalities so that inclusive solutions can be imagined and implemented.

Below, read about where and how inequality shows up in our societies, lifting some communities up while pushing others behind – and about what can be done to counteract it and ensure a peaceful, prosperous future for all.

1. Inequalities in sexual and reproductive health and rights are everywhere.

In Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, Alia* and her husband were told that it was “undesirable” for them to have a baby. The reason? They were both blind.

Women and girls with disabilities often face discrimination when it comes to sexual and reproductive health, limited access to services and exclusion from comprehensive sexuality education. Some are even forcibly sterilized.

The particular challenges Alia and other women with disabilities face during pregnancy and childbirth reinforce one of the report’s main themes: That access to health and rights vary greatly from one region, country and person to another.

Disability status represents just one facet of identity that affects the right to health. Geography is another, with women in Africa around 130 times more likely to die from pregnancy complications than women in Europe. And as for women and girls from ethnic minorities, disparities in health-care access were found in all countries surveyed for UNFPA’s report.

2. Progress on sexual and reproductive health for all is stalling, and by many counts, unravelling.

For nearly 20 years, the global annual reduction in maternal deaths has been zero – meaning there has been no progress. Meanwhile, one quarter of women today report not being able to say no to sex with their husband or partner.

This means that despite investments, advocacy and rafts of legislation, women’s ability to exercise decision-making over their own bodies is diminishing. And while barriers to health have fallen quickly for the most privileged, they are standing firm for the most disadvantaged.

“Even in better-off countries, maternal death rates are higher among communities that continue to confront racial and other prejudices in everyday life,” UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem said in her World Health Day statement. “We can and must do better.”

3. Sexual and reproductive health and rights are being politicized – and opinions polarized.

As half the world goes to the polls this year, many leaders have decided to base their political strategies on sowing division.

Anxieties over migration as well as low- and high-fertility rates are being weaponized by some policymakers to strike down sexual and reproductive health and rights agreements. Meanwhile others are making their legal systems less equitable by decriminalizing female genital mutilation or restricting the rights of LGBTQIA+ people, for instance.

Harmful stereotypes about women, girls and people with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities are too often peddled to justify gender inequality and homophobia, with dangerous consequences. As Efram*, a refugee from Syria who was struggling to access sexual health care in a new country, explained to UNFPA: “I can’t tell anyone that I’m gay because of the stigma. We are not recognized, and we don’t have any kind of rights”.

4.But there is hope: Where inequalities exist, community leaders are helping to bridge gaps in services.

Gender inequality, racial discrimination and misinformation are deeply embedded in many health systems: UNFPA research has found that in the Americas, Afrodescendent women are more likely to die during childbirth due in part to racist abuse in the health sector.

For these reasons and others – including cost and distance to facilities – Afrodescendent women may avoid going to hospitals for health care. “It wasn’t the environment I wanted,” Shirley Maturana Obregón from Colombia told UNFPA about her birth plan.

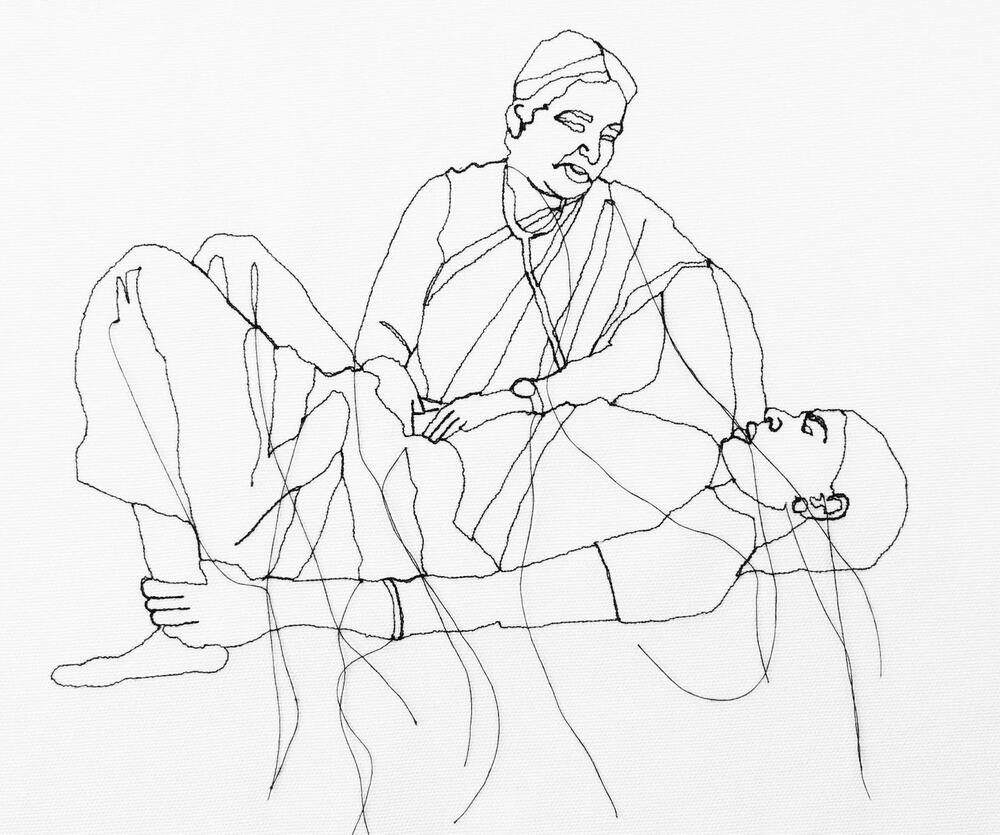

Instead, she delivered with a partera, a traditional birth attendant and practitioner of knowledge ancestral to Colombia’s Afrodescendent community.

Parteras provide culturally sensitive care among Colombian communities that remain largely disconnected from the country’s formal health system – and for whom getting to a doctor can require expensive travel across hazardous, conflict-affected terrain.

Ms. Maturana Obregón said her delivery with a partera was beautiful and unforgettable; she later became a traditional birth attendant herself. “We are there, making women’s dreams come true,” she said.

5. Progress is achievable, but we must reject division and embrace collaboration.

UNFPA’s report shows above all that we cannot divide and conquer on our way to ensuring universal health and rights. Rather, we must find political consensus, tailor solutions to communities and mobilize urgent funding to achieve our aims.

Grassroots leaders are essential to this work: Sarah Sy Savané, who advocates against female genital mutilation and child marriage in Côte d’Ivoire, says programmes aimed at eliminating harmful practices are designed by people working in the communities they target. “Safe spaces, husbands’ clubs and other interventions are making a real difference, shining a light where young girls thought they had no rights,” she told UNFPA.

Initiatives like these have tangible impacts, but they need more support. Spending an additional $79 billion in low- and middle-income countries by 2030 would avert 400 million unplanned pregnancies, save 1 million lives and generate $660 billion in economic benefits. Training more midwives could also prevent about 40 per cent of maternal and neonatal deaths and over a quarter of stillbirths.

Funding saves lives, while a lack of investment endangers them.

The truth is that inequality is everywhere we look – and once its devastating consequences have been revealed, they cannot be unseen. As UNFPA Executive Director Dr. Natalia Kanem said, “We have every reason to act – for human rights, for gender equality, for justice and for the world’s bottom line.

There is only one way to achieve a future of dignity and rights for all: By working together.”

Source:https://www.unfpa.org/